It’s now more than 35 years since Windows launched in November 1985, 18 months behind schedule and almost three years after Apple’s Lisa had introduced the first commercial GUI. It wasn’t exactly a hit; it flopped commercially, while reviewers criticised its performance and wondered whether some of its most powerful features were really that useful.

Yet less than five years later Windows dominated the operating system market, running on over 70 per cent of all personal computers sold. You can see Windows 1.0 as the ugly duckling that was to transform into the, well, still gruesome but enormously successful swan.

Making Windows

Windows began its journey in the autumn of 1982. Microsoft’s CEO Bill Gates was already aware of research into mouse-driven, graphical user interfaces at the legendary Xerox PARC, and of Apple’s continuing work on the same principles.

However, the story goes that Gates attended the autumn 1982 Comdex trade show in Las Vegas, where he saw VisiCorp demonstrate Visi On: a GUI for the IBM PC. Gates is said to have watched the demo several times, back-to-back, before suggesting that other Microsoft personnel needed to come out to Comdex and take a look. If GUIs were the future, Microsoft wanted a piece of the action.

At this point Microsoft wasn’t the huge tech monolith we know today. It was still a small company that had grown successful on the back of Microsoft BASIC and MS-DOS.

Gates saw an appetite for a new and easier way to work with the personal computer, and that rival systems were either too expensive – an Apple Lisa cost around $10,000 US, while you could buy a PC for under $3,000 – or too demanding in their system requirements.

If it wasn’t bad enough that Visi On needed a staggering 512KB of RAM and a hard disk, its applications needed to be coded in a specific version of C using Unix tools. This left space for an alternative.

Gates hired Scott McGregor, one of the key developers at Xerox PARC, and set a team to work on a project codenamed Interface Manager. Crucially, it wasn’t seen as a complete OS, but as a graphical environment that ran on top of MS-DOS. In November 1983, Gates announced Windows and set its release date for April 1984.

The hype said Windows would bring a new way to use PCs. It wouldn’t require a hard drive – just two floppy disk drives – and it would run with just 192KB of RAM.

By December 1983, an early version was previewed for an article in Byte magazine, with its writer, Phil Lemmon, arguing that ‘Microsoft Windows seems to offer remarkable openness, reconfigurability and transportability, as well as modest requirements and pricing’. The result, Lemmon thought, could bring computing to a new, non-technical audience.

Why, then, did it take another two years to get finished? For a start, there were some major technical challenges. When development started, standard CGA screen resolutions were limited to 640 x 200 in monochrome, and it was only with the development of EGA graphics boards in late 1984 that you had enough pixels to make Windows effective.

The slow speeds and limited capacity of floppy disks had an impact, while the Intel 8088 CPUs used in most PCs weren’t exactly bursting with firepower.

Perhaps worst of all, there was a challenge in building industry support. As Gates said in 1983, ‘the primary focus of the company and the speeches I gave, the promotion I did, was to get people to believe in the graphics interface whether it was Macintosh or Windows, and that was a tough thing because people like WordPerfect and Lotus refused to put the resources into doing applications’.

Some believe that other factors were in play. By 1984 Microsoft was working with Apple on Macintosh software, and had signed licensing agreements for specific UI elements, but not others, including overlapping windows and the Recycle Bin.

It’s possible that Microsoft reworked Windows to avoid including these elements and triggering future litigation. If so, Microsoft wouldn’t admit it. A November 1983 article in the US computing mag, Infoworld, suggested that Microsoft’s Steve Ballmer saw tiled windows as delivering a neater desktop.

A development disaster

Whatever the case, the development of Windows was definitely troubled. Tandy Trower came in as the product manager in autumn 1984, at a point where Windows was seen externally as vapourware and internally as an embarrassment.

Trower even saw being put in charge of the project as a step towards getting fired. By this point Scott McGregor had resigned, and while the core components were in place, elements of the design and the look weren’t working. More seriously, there weren’t any applications.

‘Even at Microsoft, getting developers to write Windows software was a challenge,’ said Trower in a 2010 interview. ‘I couldn’t even get my former team to build a version of BASIC.’

However, there was a prototype of a simple bitmap drawing program, while Trower persuaded Gates and Ballmer that Windows needed a set of simple applets, including a word processor, calendar and business card database.

What’s more, Trower made it a requirement that Windows could run existing DOS applications. This in itself proved awkward – many DOS apps exploited tricks or workarounds that caused problems for Windows memory management – but it was a major boost to Windows in the future.

By the early summer of 1985 Windows still wasn’t finished, but Ballmer decided to release a ‘Premiere Edition’ to application developers and members of the press. The team went into crunch, to the extent that one young program manager, Gabe Newell (yes, that one) started sleeping in the office.

Even at the last stages, new defects were found in the memory management code, delaying the release even further. It was only in November that testing Windows was finished, to be released at Comdex 1985 with a comedy roast where Microsoft poked fun at its own product’s lateness.

Maligned and misunderstood

You might have expected the response to be rapturous, but – as with so many Microsoft products – there was disappointment and bemusement. InfoWorld ran its review with the headline ‘Windows Requires Too Much Power’ and gave it 4.5 out of 10.

A piece by Erik Sandberg-Diment for The New York Times called Windows extremely memory-hungry. ‘Running Windows on a PC with 512K of memory’, he noted ‘is akin to pouring molasses in the Arctic. Also, the more windows you activate, the more sluggishly the program makes its moves’.

Most of all, pundits weren’t convinced that Windows solved any genuine problems. Some didn’t see the point of the mouse or the GUI. Sandberg-Diment had his doubts about dialogue boxes, suspecting that most people would prefer ‘a more direct means of executing commands.’

He also felt that multi-tasking was a waste of effort. ‘Most people use but one program most of the time, if not all the time,’ he suggested. That’s aged well.

Using Windows

So how successfully did Windows 1 lay down the foundations for the Windows we know and sort of love today? Well, it has to be said that it’s a very different experience. There’s no desktop and the management of windows is incredibly primitive.

While it is mouse-driven, icons don’t play a starring role. Instead, you launch applications by double clicking on a list in the MS-DOS Executive – a simple file manager that lists not just the programs, but all your MS-DOS files.

The first application you launch occupies the whole screen, and subsequent applications split the screen into two, three or four. Once windows are in place you can close, maximise or resize them, or move them from one half or corner of the screen to another.

But with no overlapping, space gets tight pretty quickly, and the size of the fonts and the blocky graphics mean you don’t always get enough room per application to make head or tail of what’s going on.

There’s no taskbar, but icons for the MS-DOS Executive and any minimised applications appear in a space at the bottom of the screen, where a double click will bring them back into view.

There’s also a Control Panel where you can set the time and date, adjust your cursor preferences, add fonts and set up your colour scheme. Of course, the EGA standard only supported a maximum of 16 colours from a gamut of 64, while only seven fonts were available on release.

Even some Windows fundamentals don’t work like we expect these days. Drag and drop is as non-existent as the old Recycle Bin. Today, we also forget how Windows was so keen to demand double clicks when a single click would do.

The menu bar is in place, with a button in the top-left corner where you can resize, move, close, maximise and minimise the window, but the latter two options are called Icon and Zoom. Even selecting from a pull-down menu is different, involving a click, button-hold, select and release process that feels utterly alien now.

The next shock is the primitive built-in applications. Calculator is a simple calculator with only the most basic functions. Calendar has a single field where you can add appointments on the hour or add alarms, but nothing else.

The Notepad is your classic no-frills text editor – and we mean no-frills – while Terminal is the kind of baffling, text-driven comms program that only ever looked good in WarGames. Seriously, people used this stuff?

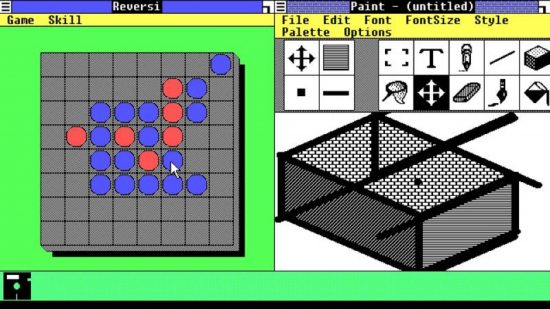

The highlights are Paint, Windows Write and Reversi, not because they’re any good but because they bear some vague resemblance to modern applications. Paint has a palette of tools, plus drop-down menus to handle fonts and options.

It also has virtually no room to actually do anything with the tools, unless you’re keen on drawing in a low-resolution, widescreen aspect ratio, or your favourite drawing subjects are sausage dogs and snakes.

Windows Write is recognisably a word processor, but there’s no spell check or anything beyond basic formatting features, much like the Windows Write we all carried on not using before Windows 95. And as for Reversi, well it’s a variant of the classic black and white disc strategy game Othello, but – let’s face it – it’s no Minesweeper or Solitaire.

What’s most striking about using Windows 1.0 now is that it feels less like an operating system than a fancy front-end for MS-DOS.

It still runs from an MS-DOS command prompt, it still works with the MS-DOS file and directory structures and it was still partly designed to run MS-DOS applications, principally because Microsoft had little faith in anyone developing native Windows ones. They were right, as until Windows 3.0 took off, barely any of the major software vendors made Windows software.

Yet there are aspects of Windows that show its potential. We’ll be kind and say that Microsoft ‘borrowed’ Apple’s concept of a clipboard, allowing you to cut and paste text or pictures from one application to another.

Microsoft’s early Windows adverts go big on copying contact details from a database and pasting them into a letter in Windows Write, then adding a graph from Microsoft Chart or Lotus 1-2-3 which, at that point, was the T-Rex of business applications.

Microsoft designed Windows to be compatible with a range of applications – not just its own – and to promote interoperability, so that you didn’t have to work with just one application, or even one specific suite. Windows wanted you to mix and match.

Microsoft also designed Windows as a GUI that could work across PCs with different hardware, and this in turn helped to make the PC market more competitive. Even at that point, Bill Gates’ ambition was ‘to create the software that puts a computer on every desk and in every home’.

Sure, Microsoft wanted to build the system software and the most important applications, but it also understood the necessity of bringing other software-makers on board.

As Gates said in 1993, ‘Our vision, we shared; we didn’t view that as some competitive edge. We just wanted to talk about it and get other people to share the same ideas so that they would help make it all come true.’

Of course, Microsoft has never been shy about monopolising, but Windows has always been stronger when Microsoft opened up and led the way. You can see Windows 1.0 as the start of that process, even if it’s not an OS that you’d want to use today.